It was a warm, gray, drizzly morning. I slipped into the cold water of Keystone Lake and swam easily for a few minutes before bobbing in the water, taking in the smell and taste of a dead skunk floating somewhere near the shore. My alarm had gone off at 4am, but only now was I fully awake.

15 minutes later, the start gun went off and the normal chaos ensued. I fought off someone on my left, unintentionally knocking him on the head fairly hard with my hand. Lost the feet we were both fighting for in the brown murk, saw that the majority of the field was veering left, away from me, and redirected my course back in that direction until I eventually fell in behind someone for a few minutes.

Despite the 56 or so starters—possibly the largest ever pro Ironman field ever assembled—I didn’t get in any major fights during those first 300 meters, which probably meant I wasn’t being agro enough. By the first turn buoy, maybe 500 meters into the swim, I found myself near the front of a medium sized group, and saw that we’d been gapped off from the next large group. Fuck. Definitely didn’t sprint hard enough in the first few minutes. I knew that the gap, which was 10 or 15 meters, wasn’t possible to close at that point. I was already at 90% effort drafting on someone’s feet. Closing five body lengths would have been doable, but not 20 or 30.

After a few hundred meters swimming in second (within my group), I went to the front and pushed hard for what felt like 10 minutes, but was probably just five, and ‘sat up’ (I can only think in bike racing terms even in swimming races) and waited for the next guy to come around. Maybe we could organize somewhat and keep our losses to a minimum.

Basically just one guy did the remainder of the pulling after that if I remember correctly, and we did hemorrhage time. That’s what happens when you only swim 10K a week. I need to rejoin masters.

The rest of the swim was agonizingly long. I kept telling myself not to estimate the distance, or time left, but couldn’t stop. We must have been swimming for at least 40 minutes by now, I caught myself guessing. Just 10 or 12 minutes to go! This was probably at the halfway mark. Maybe.

Eventually we reached land and ran to our bikes. Dizzy, disoriented, not having any idea what the gap to the leaders or the next group was, I pulled my helmet on and set out for four-odd hours of uncomfortable bike riding.

I exited T1 a few seconds behind Sam Long and a few seconds ahead of Joe Skipper, and within a mile we found ourselves working together, riding hard into a thin, misting sheet of rain that made seeing through our fogged visors nearly impossible. I felt good, and pushed well into the mid 300s and low 400s when I was on the front. The hilliest section of the race was in the beginning, and we used that to our advantage to claw back time on whomever was up the road. I, personally, didn’t really have any clue where we were in the race, position- or time-wise. I knew that a group was maybe five minutes up the road, and that we weren’t gaining on them, but that we were gaining on, and passing, others as we worked, each taking five minute pulls at the front of our little trio.

The road surface was good at times, and complete shit at others with half of the largest potholes haphazardly marked with orange spray paint, and others submerged in three inches of rainwater. Before major descents or corners, I used my index finger to wipe away the fog inside my visor for a pinhole view of the world. I enjoyed the rough conditions. A smooth, flat, straight road is the absolute worst.

Eventually we caught sight of an enormous group up the road on a straight section of the course as they climbed a gradual hill off in the distance. I hoped that they were the leaders, but deep down knew that they weren’t (a few miles earlier I heard that the leaders were still somehow five minutes or so ahead of us).

Joe was in the lead, with myself in second, when we caught that huge chase group of 20 riders. We bombed past them on a straight, fast descent, light rain still coming down from low-hanging gray clouds. Joe slid out in the corner and crashed, either taking it a bit too fast or braking too late. As I exited the corner, I surged the rest of the way to the front of the group and attacked, hoping to get away with Sam, Chris Leiferman, and a few of the other strong cyclists that I’d noticed were in the group.

Sam and I got away eventually, with him countering my original attack with a massive pull of his own. Unfortunately, the course flattened out here (and remained pretty flat for the rest of the race) and we were reigned back in by Bart Arnout and, among others, surprisingly, Joe—who’d made a superhuman effort to get back on his bike and work his way through the field of strung out riders.

For a number of miles, I continued pushing the pace, hoping to cause some sort of split, before I finally conceded and fell back to fourth or fifth wheel. I hadn’t brought enough food with me, and with no special needs service at this race, I had been rationing calories for the last hour. I could feel my energy fading, even though we’d only been riding for around two hours and 40 minutes. But with an average power of 315 at that point in the race, I’d been burning through glycogen at a rapid rate. I sat in and tried to conserve energy, hoping that I’d be able to make it on the 400 calories I had left, and Gatorade from feed zones.

By hour three, as I sat in the pack of 13 or 14 that were left after our attacking, I realized how futile it would be to go back to the front and pull (especially since I was just about out of food). Nearly everyone in the group was a faster runner than myself (on paper anyways) and seemingly only four guys were doing any work (Chris, Bart, Sam, and Joe). Everyone else was just sitting in, getting 20 or 40 watts for free. With such a huge field, having these types of flat courses makes no sense if Ironman wants a ‘non draft’ race. It is truly incredible how little work you have to do when you’re eight or 10 guys back from the front when everyone is 5-10 bike lengths separated from each other. Every Ironman event either needs 8,000 feet of climbing or more to break things up, or the draft zone needs to be doubled to 12 bike lengths.

At last, I managed to grab all three gels a hero of a volunteer held in his hand as I went by in one of the final feed zones—this was the first volunteer I saw all day who was handing out gels. I knew in that moment that my race was temporarily saved. Note to any future volunteers out there: be like this guy! A fist full of Maurten gels at mile 90 is much prefered than a fucking quarter of an unpeeled banana. I downed two of the gels (each with 100mg of caffeine), finished the last of my Clif blocks, and continued to be as lazy as possible. I needed the sugar to hit soon, otherwise I’d be screwed when we came off the bike. 15 minutes later I took the final gel and continued forcing down the last of my Gatorade as we came into the final half hour of the bike leg.

I came out of T2 in third (within our group) and immediately felt the race slipping away from me as a chest cramp burrowed itself deep into my rib cage. I’d forgotten to turn my watch on to find satellites before we got off the bike, so I couldn’t see my pace, which was a good thing because it would have only disheartened me even more. Sam passed me as Joe, Bart, and Jan Van Berkel began disappearing up the road. Miraculously, as we made our way beneath the skyscrapers of downtown, the chest cramp began to fade. I surged back up onto Sam’s heels, passed him, and continued the surge past Jan, Bart, and Joe. I began feeling stronger and stronger, and threw out any previous race plan I had of “just” a top 10. The new plan was to win, or get on the podium, as crazy as that was.

By mile three or so I heard that I was gaining on everyone except Patrick Lange in first place (in hindsight I’m not sure if that was true), and that the gap to him was around four minutes. Excited, I carried on, somehow unfearful of blowing up. The first few miles of virtually every race I’ve done have been the worst miles due to chest cramps, and I guess I had it in my mind that because those miles were behind me, I was somehow capable of running a 2:37 marathon (or thereabouts), which was the pace I was currently on. In retrospect, this was idiotic.

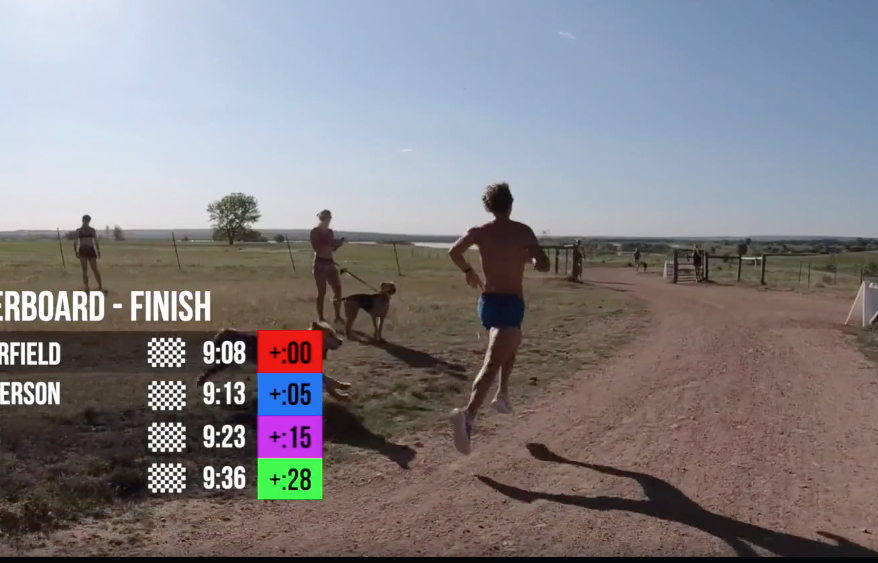

A mile later, Joe, Bart, Sam, Jan, and Kristian Hogenhaug caught me. Joe quickly organized everyone into a reverse Indian run (I’m not sure if there’s a more appropriate name for this now in 2021), with the leader taking a one minute pull before falling to the back of the line. We fought a very slight headwind as we ran along the mostly empty bike path that paralleled the Arkansas River, the few spectators that made it out there that early yelling splits and encouragement that we were gaining on 2nd through fourth place.

My sunglasses had fogged over immediately out of T2 but I kept them on. Like blinders of a racehorse. Focus. Breathe. Relax. Fight the new chest cramp that’s forming and growing rapidly like a tumor near your heart. Breathe. Stare directly at the feet of the person in front of you. Stop clipping Bart Arnout’s heels. With rain still drizzling down and my mind tuning out everything but the sounds of our panting breaths and wet shoes slapping the pavement, I finally found the feeling that I’ve been seeking for nearly two years.

By mile seven-ish, shortly before the turn around, Van Berkel broke up our group and I found myself still on his feet. We got a glimpse of Lange, now five minutes ahead, as well as positions two through four (Florian Angert, Antony Costes, and Daniel Baekkegard) all of whom were looking somewhat ragged. We’ll catch them, I realized. At least, if I could sustain this pace. But obviously, I could not.

By the turn around at mile 8.5, I’d fallen back 10 seconds and latched onto Joe as he passed me, desperation setting in as my legs started to weaken. Less than a mile later he dropped me and I was on my own. I’d been fueling just fine on the run so far, but I felt my quads losing strength at an amazing rate. Not cramping, but just seizing up, the muscles no longer working properly. I stubbornly continued running somewhat hard. Maybe if I’d slowed to 7:00 pace for the next five miles, I could have recovered and salvaged my race for 9th or 10th. But I doubt even that would have saved me. Running those first 9 miles at 6:00 pace was a huge mistake.

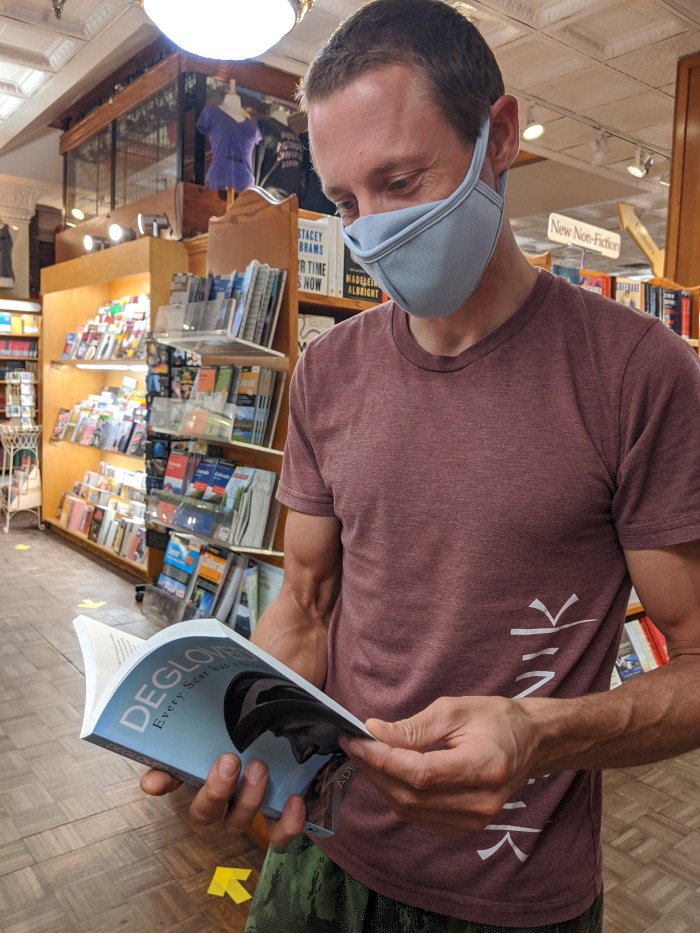

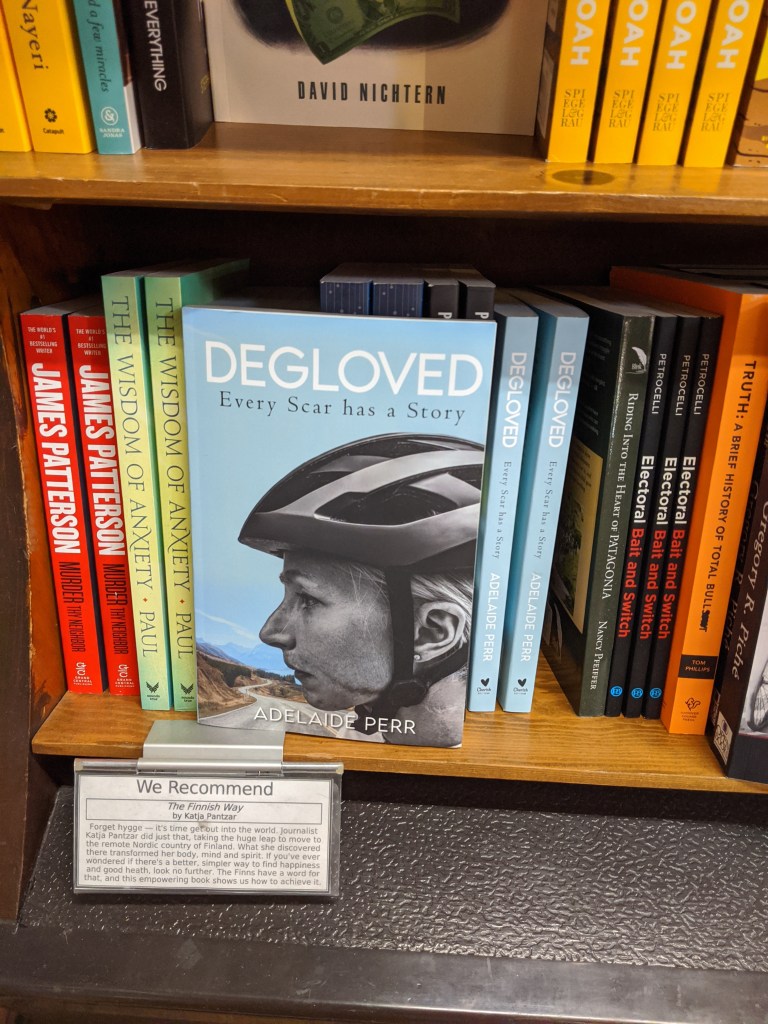

I didn’t truly fall apart until mile 15, at which point I began jogging. Not too long after that, I began walking. My legs were brittle bricks, so weak and fatigued that even walking was difficult. I shuffled and walked my way to the finish line for 10 more miles, getting passed by age groupers, on their first lap, both young and old, wondering how things could have gone so wrong so fast. Wasn’t I just up there battling for 5th place or better? Proper fueling on the bike was a bit of an issue. Not having enough run volume in my legs the two months before the race was a bigger issue. But it took until yesterday, as Adelaide and I drove home to Boulder, for me to fully realize that the major blunder was simply trying to run a sub 2:40 marathon when I’ve only done one other marathon (as a race) in my life, and that was two years ago, and it was 2:50 something (albeit at altitude).

So let that be a lesson to all. Be realistic. Be cautious. Never believe in yourself that you’re capable of greatness, because you will almost certainly fail! What you’re currently doing in life is probably the highlight—your peak—so just appreciate this next decade before climate disaster collapses civilization as we know it.

While agonizing and utterly demoralizing, walk-jogging the final two hours of the marathon was a good lesson. Maybe not a good lesson, per say, as I did make a conscious decision to risk it all for a chance at the podium, but certainly a good fitness marker of where I’m at. You never truly know until you race.

I plan on doing Lake Placid, which has some actual decisive-looking hills, at the end of July, which will give me enough time to recover and do a full buildup—this time with more than just two 50 mile run weeks. By then I’ll have forgotten any pacing lessons I learned last weekend, so look for another summary just like this one in eight weeks time.

Thank you volunteers, Ironman staff, photographers, spectators, the competition, and everyone else that helped make this event so memorable. And to Adelaide and Maybellene of course.